There is a big difference between hearing and listening. An even bigger difference between listening and listening actively.

In the 2 videos below I’m going to show you several ways you can deepen your relationship to the music you’re exploring.

Part 1 – Focus & Content

Part 2 – Context

What else was going on in 1971? What I love about this process is it makes Joe’s recording seem less like “jazz that happened back then” and more like a current event.

Jazz didn’t happen in a vacuum

Music is a language. Jazz is a language within a language. It has references and relationships both to its own genre and the time and place in which it was created. To ignore this is to miss a boatload of information.

Music is a language. Jazz is a language within a language. It has references and relationships both to its own genre and the time and place in which it was created. To ignore this is to miss a boatload of information.

All too often musicians trying to become skilled improvisers spend time and energy on their instruments but little to no time developing their listening skills. I’m not even talking about ear training.

This is silly.

If we learned to speak this way we’d all sound like Nell. It’s the musical equivalent to spending all your time practicing the motions your mouth can make, but never hearing people speak, or have conversations.

And make no mistake, jazz is a conversation.

You probably didn’t learn how to listen in school

I went to a performing arts high school with a nationally-ranked jazz band. The director of that band once (infamously) remarked that a student needed to listen to “Giant Steps” by Miles Davis.

And that was at an “arts” magnet school.

Luckily, I grew up in a town with a thriving jazz scene, and the players in that scene showed me what to listen to and for. That made all the difference in my development.

Less is more

Back then we had CDs. And not many of them. Not compared with the ocean of music freely accessible today to anyone with an internet connection or smartphone.

But we coveted the music we got our hands on. Our car’s seats, floors and glove compartments were littered with CDs (and tapes!). We listened to the same recordings until we knew every player’s part by heart. Every nuance. We poured over liner notes to learn every detail about the session.

That type of information-gathering is important. It helps you form a complete picture of what circumstances the music was created in.

Ironically, it’s easier now than ever to collect this information, but requires more effort because A) there’s so much, and B) it’s spread all over the web.

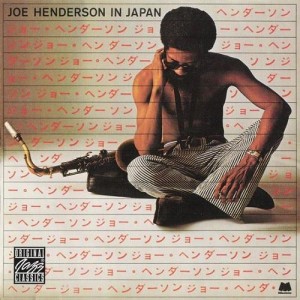

An example: Joe Henderson In Japan

I want you to listen to this track. Listen as you would normally. When it’s over, think for a moment about what you noticed; what you take away from it.

Joe Henderson – tenor saxophone

Hideo Ichikawa – electric piano

Kunimitsu Inaba – bass

Motohiko Hino – drums

Joe Henderson in Japan… is one of the handful of records from the late Sixties and early Seventies to be studied like a textbook by the most advanced young jazz musicians. It’s that kind of a record.

Now what?

Today there’s a near infinite supply of music and information. And that’s the rub: how do you process it all? How do you know what to listen to and for?

You don’t. There’s just too much.

Instead, narrow your choices. Choose one artist, one album, even one song. Listen until you’re sick of it. Then listen a bit more. You might just find the answers you’re looking for.

– Bob

Thanks, Mark! And you’re right, there’s no limit to the depths one can go on this.